By Adam Turl

The following notes are from a presentation I gave at the Left Coast Forum, Los Angeles Trade and Technical College, in August 2018, as part of a workshop on “Art, Gentrification, the Right to the City,” with fellow panelists Alexander Billet (a fellow editor of Red Wedge Magazine) and Magally Miranda-Alcazar (anti-gentrification activist and editor at Viewpoint magazine).

***

I am going to be more schematic than I would like due to space and time constraints. And I want to be clear that this talk, on “gentrification and the weak avant-garde,” is about one particular aspect of a larger discussion. I will focus on the fact that art, even the art of the “art world,” is a human necessity. But the way art is currently organized as an industry, and the ideologies that surround it, fail both the majority of artists and the working-class. The art economy does not even materially support the majority of artists (or even a sizable minority of artists). Art has been weaponized as a tool in the displacement of the working-class of post-industrial cities. And this utilitarianization of art betrays even a modern bourgeois conception of art. The weak avant-garde has become hostile to values external to capitalism; and is opposed both structurally and ideologically to even pre-neoliberal conceptions of art. Lastly, this weak avant-garde is not a monolith but itself is divided (ideologically and materially).

The start-up capital for capitalism came with three great historic crimes; colonization, the slave trade and the enclosures. The latter privatized common lands, and, by evicting peasants, created the first proletariat. The bourgeois approach to land has always been concerned with land but also capital’s broader labor needs.

In hunter-gatherer societies art served a dual social-spiritual function. As Ernst Fischer argues, what we now call art was part of development of social knowledge by small egalitarian groups. Stories, sculpture, painting, myths, became part of a proto-philosophical negotiation between known and unknown, between individual and collective. Through these, people imagined being other people; and possible explanations for all that was not yet mastered or explained – death, love, sickness, the randomness of the universe.

In pre-capitalist class society art was tied to performances of the church and state. Its pre-historic social and existential functions remained but were shaped primarily by the ruling-classes. Of course a bifurcation developed between ruling and folk arts, and there were intermediate arts as well. But as Walter Benjamin and John Berger argue such art was tied to its place in the world.

With capitalism the art economy changed. Art became a commodity. Printmaking and photography freed the image from context even more. Artists, once supported by the church and state patronage, became free agents producing work on a speculative basis. With art no longer directly serving church and state the bourgeoisie developed their ideal of “art for art’s sake.” Capitalist individualism raised the rhetorical status of the artist to “genius” – individualizing pre-modern ideas of inspiration. This reflected both revolutionary impulses as well as the interests of the new ruling-class. It led to the creation of art museums. The Louvre was made public in the course of the French Revolution.

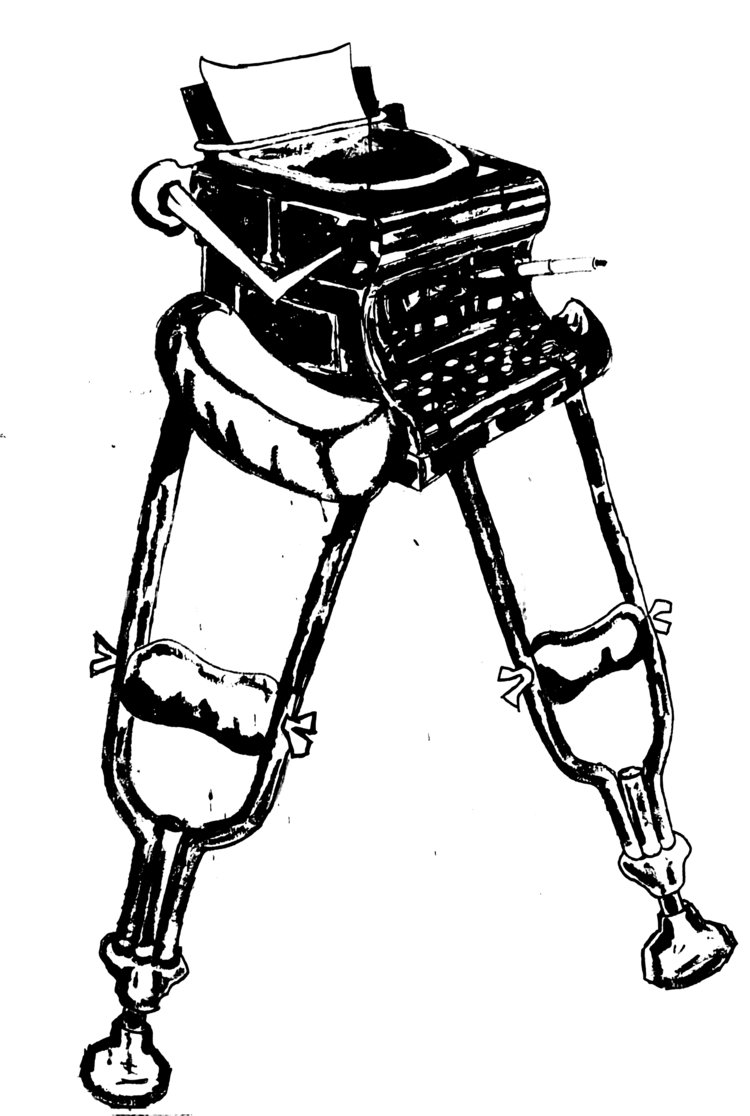

But artists found themselves in a new contradiction; increasingly free to pursue self-expression and social commentary; also increasingly free to starve to death. This produced the first oppositional avant-garde – the Romantics – who despised the utilitarianism of the new order. A succession of avant-garde movements followed; negotiating the role of art in a world of constant cultural and technological change; and struggling for a rapprochement of art and everyday life…

Within this a significant minority of artists came to identify with socialist, Marxist and anarchist ideas, seeking rapprochement through social revolution. The high points of this “Popular Avant-Garde” were the inter-war period with the Constructivists in the USSR, epic theater in Weimer Germany, the Mexican muralists, etc.; and the liberation and anti-colonial struggles of the long 1960s.

To condense history even more; with the neoliberal turn the avant-garde became what Boris Groys describes as a “weak avant-garde”; avoiding the strong images of popular and classical art, and the strong politics of modern art. The patronage of modern art had been a hodge-podge of left-wing, liberal and conservative governments, bourgeois collectors, declassed aristocrats, even socialist parties and trade unions. As the 20th century waned art patronage was largely reduced to the bourgeoisie and the bourgeois state. The industrial working-class (in the “west”) and its mass socialist movement seemingly disappeared. Post-modern “anti-ideology” took root in almost every art school. The art market was increasingly tied to finance – and public funding wed to utilitarian capitalist needs. The result was an avant-garde that looked like the modern avant-garde. But instead of aesthetic innovation, individual expression and social critique, it acted as neoliberal aesthetic management.

One of the lessons of modern art is that the meanings of art are tied to what surrounds it. In effect, each image acts as if as if it is part of a larger montage. The siting of artwork, and its relationship to gentrification, are part of its meaning. But throughout modernism the avant-garde had little or no relationship to what could be called gentrification.

Gentrification does predate the 1964 coining of the term – to at least Haussmann’s 19th century reconstruction of Paris. And as Megan Day observes, citing Robert Fitch’s The Assassination of New York, the plan to rid Manhattan of its working-class dates back to the 1920s. In the 1970s, with the neoliberal turn, real estate interests dovetailed with broader ruling-class needs. Capital no longer needed a large urban industrial working-class; but it did need to make room for new financial and technical specialists. It is at this point that art begins to play a significant role in US gentrification.

After WW2, New York began expelling industrial workplaces from Manhattan creating underused industrial zones and related problems in adjacent working-class housing. Thousands of artists moved into warehouses and garment factories. The majority came from other parts of the city and other cities (as opposed to suburbs).

The press was soon promoting a new bohemian Montmartre on New York’s Lower East Side. Montmartre itself had been a stronghold of the Paris Commune and a place where artists, workers, socialists, declassed aristocrats, trade unionists, anarchists and free-thinkers mixed together, in a manner deemed threatening by the Parisian bourgeoisie.

New York capitalists, of course, had no desire to create such a thing. What they found in art was a cynical moral appeal (which also happened to add aesthetic value to real estate).

The relationship between gentrification and art is wrought. Art is complicit but not determinant. Moreover, art world discourse on gentrification, is often inflected with a distorting liberal moralism. In the 1984 October essay, “The Fine Art of Gentrification,” Rosayln Deutsche and Cara Gendel Ryan describe the gentrification as the actualization of bohemian and romantic art ideals in opposition to working-class and poor people. This conceals that the gentrification process often negates those ideals.[1]

Historic avant-garde and Romantic designs were for the unification of art and daily life and, in the case of the latter, hostility to capitalist utilitarianism. In gentrification “art” becomes entirely functional (in its false lack of function) and structurally hostile to the daily life of the working-class.

Deutsche and Ryan also present “artists” as an undifferentiated mass –variations in class, geographic origin, race, gender, sexual orientation, are ignored. Likewise, differentiation in the affected neighborhoods goes largely unaddressed.

These aspects of Deutsche and Ryan’s argument invert the ruling-class narrative – which, of course, greeted the historic gentrification of the Lower East Side in entirely colonial terms.[2] The East Village was described as a “Neo-Frontier” and the artists who moved there described as “heroes.”[3]

Richard Florida’s The Creative Class (2004) aimed to generalize from this “art-led” gentrification. His concept of the “creative class” flattens the actual processes at work in gentrification while also providing ideological cover. For my purpose here, it conceals the precariousness of contemporary labor under the mythology of the heroic artist; and conflates artists and workers with capitalist entrepreneurs and the professional middle-class.

Artists do not really fit into any of these categories: precarious workers (targeted for displacement), capitalist entrepreneurs (who marshal finance capital into economies of exploitation) and middle-class professionals (who usually have, in relationship to overall capitalist production, far more wealth and autonomy than artists, although they often have a similar educational background). They also bring the coup de’ grace in urban displacement.

Artists come from all social classes. They are middle-class in relationship to the art market. But in relationship to overall capitalist production they often tend to be precarious workers as well (because only a few thousand visual artists in the US actually make a living as artists – about half in New York City and a third in Los Angeles). At the same time, however, their largely unpaid aesthetic work valorizes neighborhoods targeted for gentrification.

Turning these relationships into an undifferentiated mass, “the creative class,” Florida provided cities with a way to simultaneously wage and conceal class conflict.

Gentrification confuses modernist aesthetics. Modern artistic strategies meant to be critical of capitalism, valorizing working-class life and neighborhoods, emphasizing authenticity, are now easily used against artists and working-class communities, translating cultural value into exchange value. Any image or cultural sign critical of gentrification can almost instantly be turned into an image or sign used for its benefit. This is true when a middle-class artist moves into a neighborhood seeking “authenticity.” But it is also true when art, organically produced by working-class artists in their own neighborhood, valorizes its surroundings.

Deutsche and Ryan argue, “artists have placed their housing needs above those of residents who cannot choose where to live.”[4] This is undoubtedly true of some artists. But not all. Part of what primes artists to be cynically manipulated in the gentrification process is their poverty. But most mainstream art world discourse assumes a priori that artists are middle or upper class. For example, Heather M. O’Brien, Christina Sanchez Juarez and Betty Marin, in a 2017 article on Hyperallergic, outline “An Artists’ Guide to Not Being Complicit with Gentrification.”[5] While well-meaning and containing some useful advice, this very framework individuates the problem and assumes a paradigmatic middle-class artist. Moreover, this does not raise how the avant-garde’s complicity in gentrification threatens art itself. This is a framework of charity as opposed to solidarity.

This is a more developed form of the usual liberal kvetching on gentrification, that as Gavin Mueller argues, “does what liberal discourse so often does: it buries the structural forces at work and choreographs a dance about individual choice to perform on the grave.”[6] The artist Anna Francis, arguing for an alternative strategy of “social practice art,” writes, “[f]ar from being an artwash, this can be a celebratory and cathartic activity – even if the outcome, eventually, is the same.”[7] In other words, gentrification cannot really be defeated, but we can try to escape complicity in our work. This is not good enough – for workers or artists.

The avant-garde is an organic product of capitalism. It exists because capitalist culture changes. The avant-garde is a site of ideological contestation. The “art world” has its own economy in which a small number of artists and art institutions take the lion’s share of profits while the majority do not. The erosion of the Keynesian state eliminated most public art funding in the US not tied to gentrification and neoliberalism. Art spaces have increasingly turned to private finance and become more culpable in the gentrification process. The ideological contradictions of the weak avant-garde are untenable. The art space cannot continue indefinitely without a non-financial “reason for being.”

The reason to outline this is to discern artistic strategies for artists against the weak avant-garde and to develop political demands that aim to drive a wedge between the neoliberal city and “art.” First of all, socialist artists need to make work that in its immediate meaning and context is opposed to gentrification. This work should champion the working-class itself, overtly embracing socialist politics. This does not mean all art needs to be didactic. Nor should art become only an appendage of social struggle.

But for art to become art again (in the best aspects of modern or pre-historic art for example), it must stop being a rarefied performance for the well-heeled, and concern itself, first and foremost, with the material, psychological and spiritual needs, dreams and nightmares of the working-class and oppressed.

Nothing artists can do as artists, however, will solve the underlying problem. Both artists and workers need mass social-democratic housing reforms – at a minimum. In the struggle for these reforms we should aim to create an objective conflict of interest between real estate speculators and artists; by tying public patronage for art to social democratic housing policies and broader pro-working-class demands.

If art and the working-class have been put into competition our goal should be to short-circuit that competition.

[1] Rosalyn Deutsche and Cara Grendel Ryan, “The Fine Art of Gentrification,” October, Vol. 31 (Winter 1984), 91-111

[2] Deutsche and Ryan, 91

[3] Deutsche and Ryan, 92

[4] Deutsche and Ryan, 100

[5] Heather M. O’Brien, Christina Sanchez Juarez and Betty Marin, “An Artist’ Guide to Not Being Complicit with Gentrification,” Hyperallergic (June 19, 2017)

[6] Gavin Mueller, “Liberalism and Gentrification,” Jacobin (September 26, 2014)

[7] Anna Francis, “’Artwashing’ gentrification is a problem – but vilifying the artist involved is not the answer,” The Conversation (October 5, 2017)